Meeting My Mother's Family

Memorial Day Week 2023

I stepped in dog shit as I got out of the car beside the first monument at the Chickamauga Battlefield, the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War, and I thought, “How appropriate.” Who wants to deal with a stinking, rotting, smear of slippery wet feces across your white tennis shoe? No one. And yet I knew I must. So I sat down with a package of wet wipes and rubbed all the little crevices, working the shit out of the cracks, surrounded by monuments to the people who’d fallen there; approximations of the time of day they died, lists of where they’d come from.

I am still processing this recent trip to Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia where I got to meet about FIFTY of my relatives for the first time. My aunt had asked me, out of the clear blue, if I’d like to go with her to meet that side of the family. You see, her mother had died when she was 12 and my mom was only 5. They’d grown up in an orphanage afterwards in Texas, so I’d never had occasion to meet any of them until now. I was elated that my aunt was willing to grease the wheels and help me meet so many of my people since I’d been wondering about them through my genealogical research these past few years as I’ve been working on healing my ancestral lineage.

Though I was excited to meet folks, I experienced so much anxiety preparing to go on this trip! I assumed that most of the relatives that I’d be meeting would be Republicans, and I tried to come up with some sort of strategy for how to be with them since I am a self-professed leftist and Social Justice Coach. 😜 I quickly found that I was not (on the whole) wrong about their right-ward leanings, and I never did come up with a satisfying, catch-all strategy for “how to be” with them. But, in hindsight, I think that was the wrong question, really.

What I can say is that, once I stepped foot inside the homes they graciously shared with me, I saw that I was in new territory, for which I had no map. Because, though I am a Texan, I have lived in California for almost as long as I lived in the city where I was born, and I am no longer accustomed to talking to, and practicing care for, conservatives. Yet they remain my people.

I am a descendant of enslavers and colonizers. I am a descendant of countless women who birthed huge families so that some of their children would survive. I am a descendant of Confederate, as well as Union soldiers. I am a descendant of the stories this nation tells about what it means to be free, in all its twisted glory.

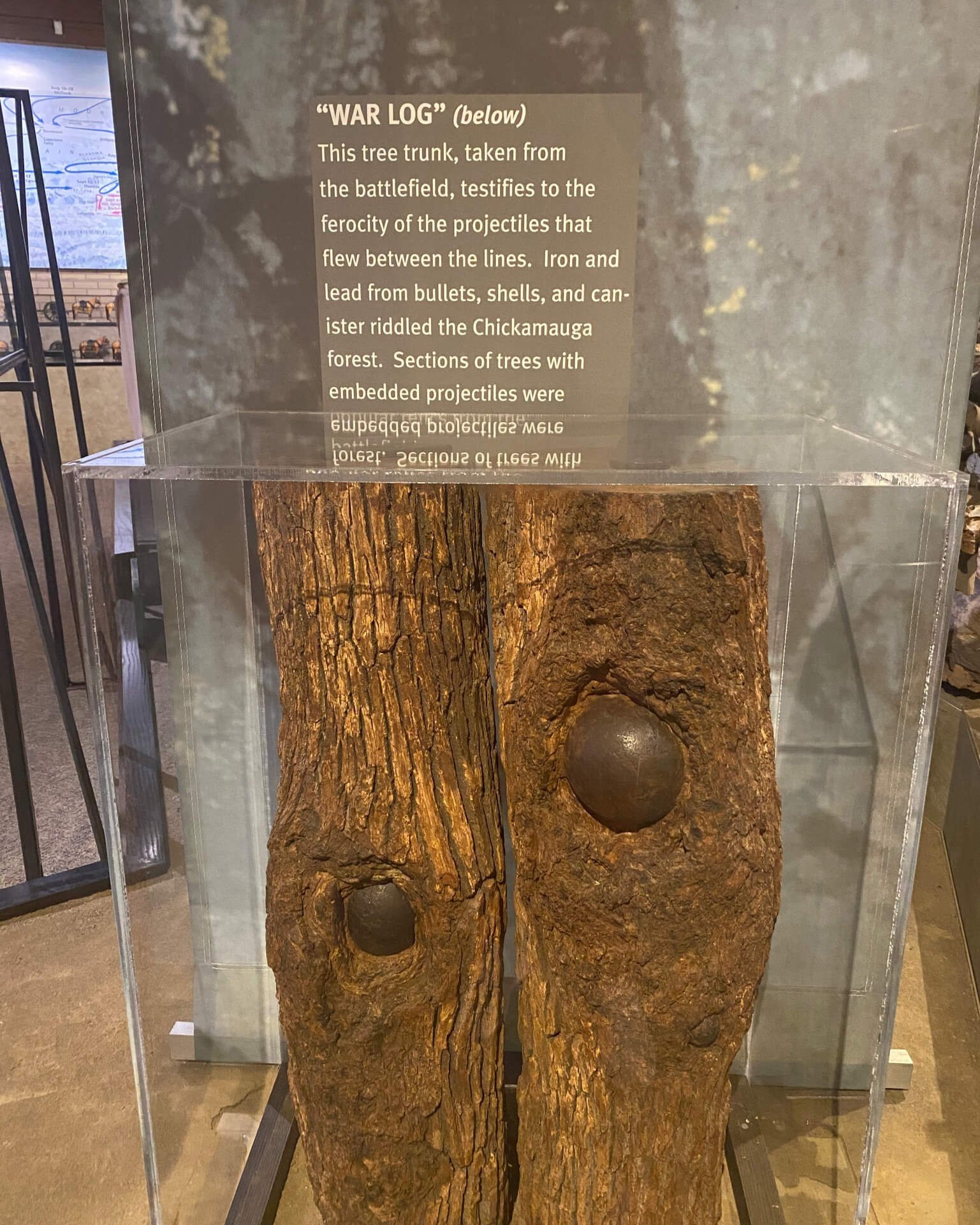

The presence of the Civil War was palpable everywhere I went on this trip to the battle-scarred lands where it was fought, so much so that it made absolutely no sense to add to the lingering sense of “Us vs. Them” that turned families and neighbors into enemies who fought each other to the death by the hundreds of thousands. Quickly, it was apparent how much the Civil War lives inside of me, too. That I needed to figure out how to listen. That I had to get to know and respect my folks before we could talk about things that we do not agree on.

This is the kind of long-distance work that I feel so many of us white people in the United States are being called to do with our families at this time in history – a prerequisite to building the healthy, connected, multiracial, just society we all deserve. Because how can we be a part of that work if we can’t first love our own families? Absolutely no one else can help us heal from these fractures. It’s on us.

So my trip was marked by warm Southern drawls and being welcomed home, but that was a dual move of generosity undergirded by defensiveness and hair-trigger avoidance of further humiliation. Understandably. We can be so hard on one another.

Each of my female relatives had some other woman – a son’s ex-wife, or an ex’s new wife – that she called a witch. And Lee and Linda each have neighbors they hate. Lee said it was about enough to make him want to shoot his neighbor with his home-made bullets for bringing “every low-life in Shelby County” out to his property. Linda said that her dog had come home with her neighbor’s horses’ blanket and that she’d whipped her ass and walked her six times around the property, beating her each time she looked in the direction of the neighbor’s property, until Linda believed the dog understood the rules of the house. There was much I saw and heard on this trip back South that made me want to draw a line and take up proverbial arms against it, but something in me knew that it was time to do something different.

Instead, I listened. Instead, I worked. I made breakfast, carried bags, shelled crawfish tails, even helped extract honey. It’s true, Lee, my Vietnam veteran cousin, makes his own bullets. He also keeps bees. Has 17 hives. Somehow, despite all the evidence to the contrary, and what I thought I’d feel about it, I found myself most fond of him: a straight, white, working-class, Republican, gun owner who asked if Nancy Pelosi was my representative when he heard I was from California.

I think part of why it went well between us is because we got to do work together. We spent two days extracting honey and talking. He helped me don a bee suit, showed me how to use the smoker, how to get the bees to leave when you’re ready to extract, how to use a honey knife and a cap scratcher, how to get a rhythm going with the bottling.

And while we worked, we talked. I heard about his concern for his autistic grandson who lives with him, and about being in therapy for PTSD from fighting in Vietnam. I found out he has a son who lives in San Diego who married a woman from Japan whose parents don’t speak English. I heard about how they try to communicate with each other because Lee doesn’t speak Japanese.

I told him about a trip I took to Big Bend, years ago, on the Texas/Mexico border and how we rode horses to the Rio Grande, paddled across, and had lunch in the kitchen of a Mexican woman who made us food from scratch before we rowed back across to Texas. I hadn’t meant it as a “teaching conversation” – I was more trying to find common ground with him around our love of camping – so it surprised me when he said, real thoughtful, “You know, it’s good to hear a story like that. That you had a good experience like that. You always hear so much about the violence and drugs on the border.”

There was something about stopping trying to prove something to one another, and just simply working together on something useful – and even beautiful – that was healing for us both. A sweetness. The honey, like Oshun pouring her blessings out on our time together.

I admit I liked impressing him by not being afraid of the bees. And though he maintained that he only keeps them for the “honey money,” I think it was more than apparent that he likes taking care of them. And I loved him for it. In the end, he sent me home with seven bottles and told me he’d miss me. The truth is, I’ve missed him, too, no matter how hard it was for me figuring out how to be around him without slipping into harshness and fighting. Something in this is healing. The wisest of our ancestors are having their way.

My mother keeps calling me to hear 10 minute snippets of what my trip was like, then cutting me off from story-telling to tell her own memories. Crying her face off about how healing it is for her that I’ve gone to meet the family she’s been estranged from since she was a little girl growing up in an orphanage after her mother died.

Like the honey once the caps are scratched off, the stories are flowing. Already she’s told me things I hadn’t known, things she didn’t know she remembered. Like the picture I have of her as a baby in the arms of Stella, her aunt – the mother of Pamela, another cousin I visited. When I told her about the picture she said, “Well maybe that’s who my wet nurse was!” For the first time she told me that her mother had been too sick to breastfeed her when she was born. That another family member – she didn’t know who – had breastfed her instead. And isn’t that just what it’s like with family? So many people whose names we may never know set things up so that we can be here today. We inherit all of it. The sweetness and the sorrow. And we get to decide what we will do next with it.

*Names of the living people mentioned have been changed to protect their privacy.